|

Tonight is Halloween. My kids will be going door-to-door getting candy, and we'll probably be handing out candy to neighborhood kids from our door as well. But October 31 is significant for more reasons than just this. October 31 is also "Reformation Day" - the day in 1517 when a monk named Martin Luther nailed 95 Theses to a church door in Germany and sparked what we now call the Protestant Reformation. (For a recommended introduction to Luther's 95 Theses, check out this book.) Here's what Philip Schaff, a noted church historian, says about the significance of the Reformation: “The Reformation of the sixteenth century is, next to the introduction of Christianity, the greatest event in history. It marks the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of modern times. Starting from religion, it gave, directly or indirectly, a mighty impulse to every forward movement, and made Protestantism the chief propelling force in the history of modern civilization” (Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church, Vol. VII: Modern Christianity—The German Reformation [1910; repr., Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1980], 1). Earlier this week, someone passed a post along to me from Ligonier Ministries. This post shares a bit more about the history of the Reformation and key players in it. I encourage you to take a few minutes on this Reformation Day of 2014 and check it out. Here's the post: "The Reformation and the Men Behind It" by Stephen Lawson Please note the usual disclaimer, that my recommendation of this article is not necessarily an endorsement of everything else on the site where this was posted.

0 Comments

Recently, Christianity Today (CT) published a web-only article drawing attention to a theological survey that LifeWay Research did for Ligonier Ministries. (I encourage you to read the whole article here.)

While the survey is encouraging in the high percentages of understanding some orthodox beliefs, other key orthodox beliefs - about salvation and the Holy Spirit, for example - weren't nearly so well understood. For example, only 42% affirmed that the Holy Spirit is a person and not an impersonal force. 29% believe God's grace precedes any human initiative in salvation - 71% either believe people first seek God or don't know. Ligonier's Chief Academic Officer, Stephen Nichols, seems to summarize the survey as revealing "a significant level of theological confusion" among those categorized as evangelicals. How should we be thinking about this? Two things to come to my mind: Last weekend in the Brookside Institute "Fuel for Faith" class, the topic for the session was "The End of the World. (Kind of.)" Jesus is coming back. History is moving towards a settled future where God wins and everything is as it should be. Beyond these foundational Christian beliefs, though, common consensus usually ends as words like "rapture," "tribulation," "Daniel's 70 weeks," "millennium," "antichrist," "Revelation," and more become part of the conversation. All of these words are often wrapped up in the topic of "eschatology" - the study of last things.

Whenever I talk about eschatology, I know some people of the people listening feed off any "end-times" discussion that uses any or all of the words mentioned above, and a certain approach to eschatology is THE lens through which they look at everything else. Others run away from anything that hints at "end times talk" because of the division they've seen it create or the intricacies involved they're not interested in. With either of these approaches, the emphasis of eschatology is often on its more speculative aspects (think charts, timelines, headlines, etc). People either love this stuff or they're turned off by it. Now, I believe talking about and discussing some of these more speculative aspects of eschatology has its place (given the right context, approach, attitudes, and goals). I've graciously dialogued about these speculative aspects with others many times. But these speculative aspects of eschatology should never take the lead in our thinking about this topic. What should take the lead? What's one part of eschatology where we NEED consensus? Transformational eschatology. Here's a sampling of some of the things I've been reading and reviewing this week. The hope is that these bite-sized sections of books, articles, blog posts, etc will stand on their own and be beneficial in-and-of-themselves. But I also hope that some of you will like these excerpts enough that they pull you into the larger work from which they've been taken.

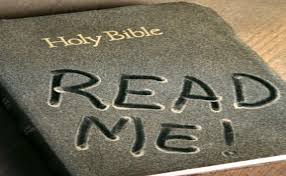

Let's start sampling: Ed Stetzer, President of Lifeway Research, author, and speaker has recently written an article worth noticing on biblical illiteracy and Bible engagement. I encourage you to check out the full article here - it's worth reading. Really. (Or, you can see a few expanded installments on the article starting here.)

Here's a short outline/summary of what he says. My hope is that this will pull you into the larger article of which this is a snapshot. We live in one of those days and ages and cultures where individualism - a good value in its rightful place - has often become ultimate. And this individuality-as-greatest-concern has seeped into the church, leading to a growing number of believers in Jesus Christ who "love Jesus, but not the church."

In the face of this cultural mindset, how do we uphold the value of the local church - a gathered body of believers characterized by certain things? The more we can stack hands on these two following "foundational beliefs," the more people will WANT to commit to and invest themselves in the local church: Here's a sampling of some of the things I've been reading and reviewing this week. The hope is that these bite-sized sections of books, articles, blog posts, etc will stand on their own and be beneficial in-and-of-themselves. But I also hope that some of you will like these excerpts enough that they pull you into the larger work from which they've been taken.

Let's start sampling: When people hear about or think of the Brookside Institute, there are three phrases I want them to associate with what we're doing in any of our classes or learning environments. These phrases are "Dig Deep," "Learn Good," and "Launch Well."

Let me briefly explain what I mean by each of these: The way we think about theology is important. I've heard theology described as "dry," or like "a brick wall keeping us confined to a small space," and more. All of these pictures influence how we approach theology and the value we place (or don't place) on it.

In this post, I'd like to suggest four images we should picture in our minds when we think of theology. These four images should be taken together and - when done so - show us why theology really is that important. (Oh yeah - just to make sure we're on the same page, my super-short-and-probably-simplistic-30,000-foot-definition of theology is this: "Looking to God's Word for both (1) guidance on/answers to key questions we're asking, and (2) a framework for knowing which questions to ask.") With that said, here are four ways to picture the value and health "doing theology" can bring: Here's a sampling of some of the things I've been reading and reviewing this week. The hope is that these bite-sized sections of books, articles, blog posts, etc will stand on their own and be beneficial in-and-of-themselves. But I also hope that some of you will like these excerpts enough that they pull you into the larger work from which they've been taken.

Let's start sampling: |

Tim WiebeChristian. Husband. Father. Pastor. Learner. Contributor. Reader. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

© 2014-2024 | 11607 M Circle, Omaha NE, 68137 | www.thebrooksideinstitute.net

RSS Feed

RSS Feed